For the past few years I’ve had a deep feeling in my gut that the specific form, style, and content of “Weird Twitter” posts represents some of the most important and interesting writing that has come out of the dogshit decades of the 21st century. It’s deep embedding within the context of online spaces feels like it is directly addressing the elephant in the room – namely the extent to which communication technology has addled and disoriented both our material reality and inner lives.

This is supplemented by a sense that the literary establishment has been generally ill-equipped to address this topic effectively due to a fixation on the novel as the premier vehicle for “important” writing. Novels struggle to depict communication technologies because to realistically portray the omnipresent and vapid relationship we have with the internet undermines the novel’s form; it short-circuits plot, obstructs its portrayal of individual consciousness, and limits environments to what can be seen and heard within a screen. However, to not depict technology at all shatters the novel’s claim to present some degree of “realistic” reflection of the human condition. So instead modern writers must constantly elude the presence of our online lives by artificially reducing the prominence of phones and computers in their characters and plot, because a novel in which someone is constantly checking their notifications for no reason beyond compulsion makes for a bad book.

Yet, I’d posit that the two most significant historical facts of our collective epoch are:

The integration of modern communication technologies into nearly every facet of our lives.

The rise of a post-cold war capitalist mode that has claimed these technologies as its own and become the primary advocate for said integration.

A pet analogy I like to trot out at parties is that the impact of the internet on our lives today mirrors the impact of the factory during the industrial revolution. Both represent a seismic shift across every level of society as to how the majority of people are leading their lives. More than this, in their newness we have no collective sense of what might be dangerous about them. At my most optimistic, I believe that people in the future will view how we interact with the internet today – its constant availability/presence in our lives – in the same way we view the use of child labour in those early factories. We didn’t know - could not have known – the damage being done to us by this new arrangement, and the extent to which we would need to fight against the forces of capital that promoted them.

I believe Weird Twitter represents the first meaningful literary inclination toward this resistance. I only joined twitter in 2017 when much of the style and ethos of this loose genre had been solidified and I immediately recognized something that spoke directly to the lived reality of 21st century life in a way I had not seen elsewhere.

What follows is an essay I wrote for a master’s level English class that attempts to formally articulate what Weird Twitter’s style is and why it’s important within this context. I’ve tweaked some of the language for readability, but it will still be essayistic in tone.

This piece was written as a rhetorical supplement or addendum to Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together, a book which brilliantly unpacks our inclination to to ascribe authenticity and meaning to relationships that are mediated through networked environments, or alternatively to relationships we have with robotic and/or digital beings that are not human at all. Alone Together describes the way in which modern online life threatens our ability to have actual authentic relationships. Towards Turkle’s conclusion she states the following:

We have already completed a forbidden experiment, using ourselves as subjects with no controls, and the unhappy findings are in: we are connected as we’ve never been connected before, and we seem to have damaged ourselves in the process. (293)

Turkle’s melancholic exploration of what this damage looks like is undertaken via qualitative psychological assessment of how networked life has affected various interview subjects. While Turkle rightly argues that authentic human social relations are the primary antidote to the harm caused by this technology, she omits any suggestion that the “damage” we are doing to ourselves online can be resisted by anything save a form of serious mindfulness that takes place at the level of the individual user.

Accepting Turkle’s basic premises, I’d like to broaden the potential avenues for resistance to this damaging inauthenticity of online life to encompass subversive humour and political commentary. I offer a qualitative analysis of “Weird Twitter” as a complimentary form of such resistance, one that aids or augments the ability to find meaning in our actual lives. This occurs firstly through a form of humour that gives itself totally to networked inauthenticity in a sort of aesthetic self-derangement that highlights the absurdity of online life. Secondly, Weird Twitter engages with the socio-political realities of an internet landscaped shaped by neoliberal capitalist market forces that Turkle is broadly unconcerned with in Alone Together.

Social media site Twitter, in which a user can post 280-character “tweets” that can then be liked or repeated by other users who see it, has been the up-until-recently exclusive platform of the “Weird Twitter” community. This term refers to a relatively small collection of users whose comedic tweets amassed a large number of followers in the early-to-mid 2010’s, and who consequently had an outsized influenced on the rest of the Twitter user base. What exactly constitutes the humour of Weird Twitter is difficult to define as it relies heavily on absurdity, subversion, and a self-awareness about online life. John Herrman and Katie Notopoulos of Buzzfeed News created an oral history of the movement, and suggest the following definitions in their introduction:

1. [An] intentionally wrong style of idiotic comedy

2. A loose group of Twitter users who write in a less accessible form, using sloppy punctuation/spelling/capitalization, poetic experimentation with sentence format, first-person throwaway characters, and other techniques little known to the vast majority of 'serious' Twitter users.

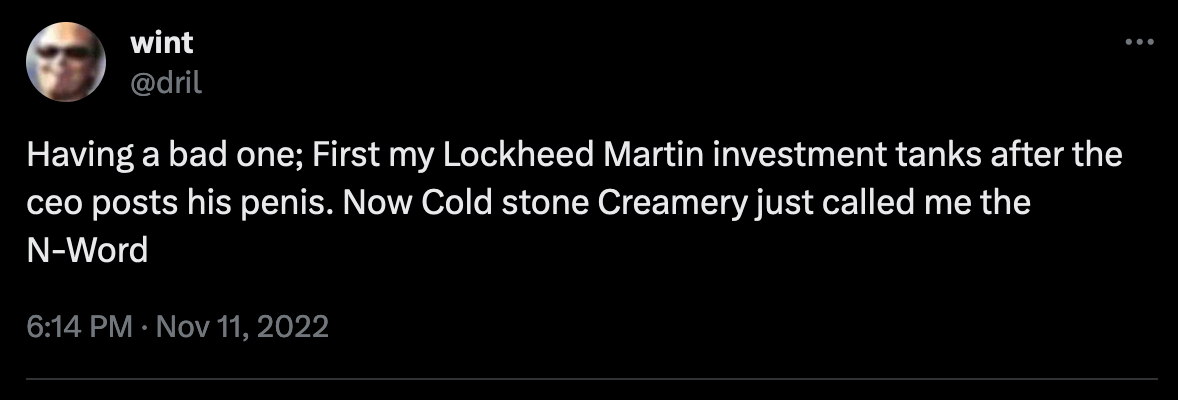

If this definition remains imprecise, the actual presence of Weird Twitter as a specific phenomenon does not, with articles attempting to define the term appearing in a wide range of online news publications such as the above in-depth Buzzfeed article, Business Insider, Michigan Daily, and Complex. While my argument is oriented towards the impact of weird twitter as a loose online movement, it will draw specific examples in the output of two accounts that have been associated with Weird Twitter by major news outlets. These are @dril and @dasharez0ne.

These accounts are exemplars of Weird Twitter in their development of an idiosyncratic comedic style in which the joke is located as much in form as it is in the content of what they tweet. The @dril account has been tweeting consistently since 2008 in the character of an aging male internet user with erratic spelling and syntax and is, “[…] narcotized by convenient distractions and delusional ambitions, perpetually mired in trivial grievances, indiscriminately vehement about matters of church, state, and McDonald’s, and, above all, almost completely inarticulate” (Marshall) @dasharez0ne is a late-comer to the Weird Twitter community, having begun posting in 2015, and tweets image-based memes with purposefully bad graphic design in emulation of a particular style of hyper-masculine online content. The account is framed as being run by a skeleton named “Admin”, whose images typically feature skeletons holding guns or riding motorcycles with superimposed text that begins with an angry or abrasive statement in the vein of toxic-male memes or bumper stickers, before concluding with a second statement that reveals Admin as actually kind, emotionally sensitive, left-wing, or simply anxious about everyday life. Both of these accounts embody Weird Twitter in their adoption of a stylistic form that locates humour in its brevity, absurd characterization, niche references, and an extreme self-awareness of being embedded in online life.

That the tweets of these accounts, and Weird Twitter more broadly, should be considered as valuable or worthy of analysis is established by critical models around micropoetries, a self-eroding category of poems that has existed in scholarship since the 1990’s and is defined here by Maria Damon:

“The word “micropoetries” confers a positive value on the unfinished nature of fragments, ephemera, and sub- or para-literary, unintentional or otherwise “unviable” poetry. Since the receptive field of and discourses about poetry range so widely, micropoetries are intensely rooted in the time, place, and context, often arising out of the cultural practices of communities on the margins of power and visibility” (3)

Damon explicitly references the potential for social media posts to constitute micropoetries, and offers a brief review of Scottish twitter users spontaneously developing a standardized insult format to tweet at US President Donald Trump after he wrongly claimed Scotland voted to leave following the 2016 Brexit vote. Within the micropoetries framework, twitter accounts like @dril, and @dasharez0ne each represent a carefully crafted body of pseudo-literary work that is profoundly embedded in the online context they operate within. Their work is highly obscured by the specifics of their various niche online contexts, and yet are all crafted for a broader audience using a variety of unique forms or conceits. This element of intentionality is particularly apparent in the two accounts explored here, as all of them post exclusively “in character”. Many other accounts associated with Weird Twitter are tied to real individuals who happen to tweet suitably abstract humour, with novelist and poet Patricia Lockwood being one of the most notable examples. In @dril and @dasharez0ne we have a concentrated body of micropoetries undiluted by the more mundane or grounded social media posts of an actual person. Their total commitment to characterization and absurd context is at the root of what makes these accounts so compelling and resonant for their audience, and a key aspect of how they resist the inauthenticity of our networked lives.

Inauthenticity is at the heart of the issues identified in Alone Together. Over the course of the second half of Turkle’s book, which is dedicated to networked environments, it becomes clear that people are drawn to online spaces because they offer us the illusion of control over our social interactions and a promise that we will be validated, so that “we can have connection when and where we want or need it, and we can easily make it go away. […] No matter how esoteric their [the user’s] interests they are surrounded by enthusiasts, potentially drawn from all over the world. No matter how parochial the culture around them, they are cosmopolitan.” (160-61). This sense of control and validation exists precisely because networked communication is profoundly shallow and unable to fulfill our need for meaningful intimacy, yet their dual allure is powerful enough to bring us continually back to our devices so that we convince ourselves that these interactions have more meaning than they do. Turkle suggests this allure exists because of the ways in which human interactions can be fraught or challenging for us.

“When we say we look forward to computer judges, counsellors, teachers and pastors, we comment on our disappointments with people who have not cared or who have treated us with bias or even abuse. These disappointments begin to make a machine’s performance of caring seem like caring enough.” (282)

Online life therefore promises a world devoid of the emotional pain our social environments cause us, and, despite this pain being essential to genuine intimacy and meaningful connection with others, we are drawn to a networked environment that promises we can avoid it. The micropoetries of Weird Twitter holds up a mirror to this impulse within ourselves by presenting content and characters that are so utterly internet-addled that they verge on total incoherence, Weird Twitter locates humour in a depiction of what life becomes when we are “too online”. It is a depiction composed entirely of a superficial connection to the world that networked life offers us, and in finding it funny we necessarily recognize this own shallowness within ourselves. Through immersion, a critique.

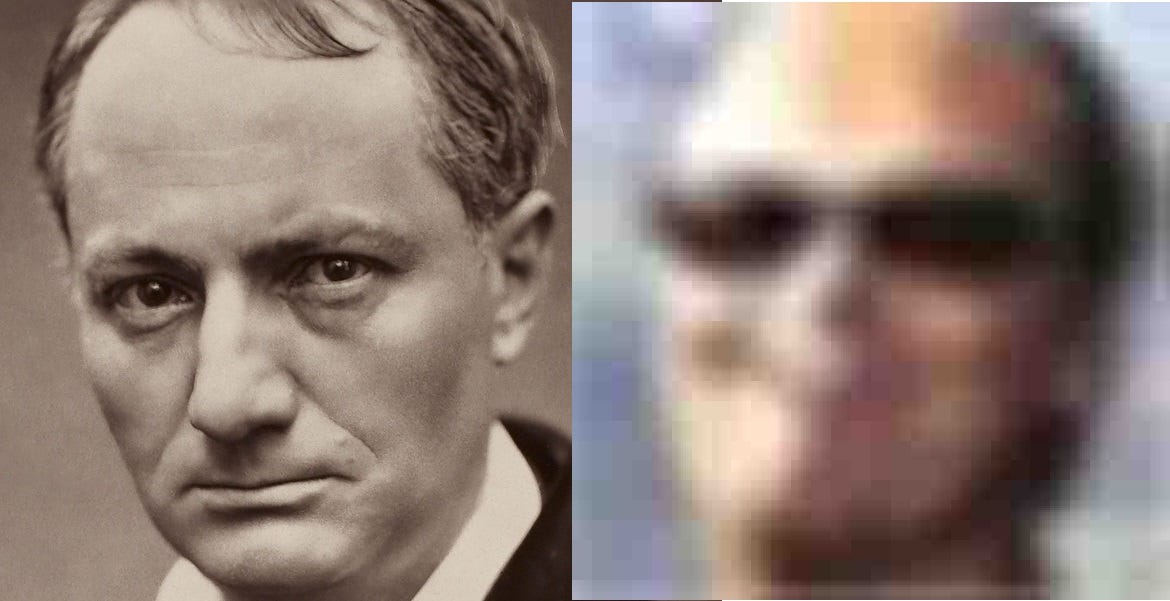

Theoretical parallels can be drawn between Weird Twitter, particularly @dril, and Walter Benjamin’s writing on the French poet Charles Baudelaire, who Benjamin presents as the first truly “modern” artist in the latter’s thematic preoccupation with the arrival of urban commodity capitalism in the Paris of the 1850’s and its effects on us: “For the first time, with Baudelaire, Paris becomes the subject of lyric poetry. This poetry is no hymn to the homeland; rather, the gaze of the allegorist, as it falls on the city, is the gaze of the alienated man. It is the gaze of the flâneur, whose way of life still conceals behind a mitigating nimbus the coming desolation of the big-city dweller” (Benjamin, Arcades, 10). Baudelaire leveraged the othering sensation of modern industrial life by immersing himself in the crowds of the city as its observer, as in Benjamin’s characterization of the flâneur. This connection to the crowd is situated within a dialectic of vaporization and centralization, “Many times, Baudelaire depicted the artist as a virtuoso of self-diffusion. Merging with the crowd, he multiplied himself through fragmentation” (Seigal 114). The “too online” persona of @dril and his micropoetic tweets reacts in precisely the same manner to the rise of networked communication in our lives. It seeks to depict someone so online that they take on the quality of a deranged prophet of 21st century life.

We associate Dril with Twitter, but he is much larger than that, he is a patron saint of the internet itself – a rare rallying point and muse for everyone regardless of affiliation or creed. It's old hat, at this point, to compare him to Donald Trump: Both are aging, endlessly aggrieved white men who seemingly do not understand the core components of the internet, yet they perfectly embody its anonymous rage, its ability to turn people into lunatics being swarmed and eaten alive by enemies and trolls. (Purdom)

Much of the writing around the @dril persona both in media and among twitter users echoes this sense of someone who captures the zeitgeist of the internet age in its totality. “Dril isn’t just anyone: his posts have largely come to define the vernacular and culture of both the internet at large and Twitter in particular. He’s the Wise Fool of online” (Stephen).

Benjamin identifies Baudelaire as exhibiting “the metaphysics of the provocateur” fuelled by “grim rage” (5). This grim rage is Baudelaire’s ethos and method of dealing with the difficulty of a changing world and, while not always present within his art, it is seen in his prose writing and, “the driven, haggard figure who stares bleakly at us from contemporary photographs” (Seigal 110). The @dril persona exhibits a similarly perpetual fury that appears to be located in his frustrated inability to merge even more fully with online life.

@dril: for each day that Arbys.com does not return to the Frames Version of their website I will go to Petsmart and kill one beautiful bird (Dril, 263)

The subtext to much of @dril’s posts is that his rage is in fact rooted in, and fuelled by, his relationship to the online world that preys upon eliciting a strong emotional reaction in its users that keeps them engaged and attentive to the shallow connections we hold online. @dril embodies the type of person that Turkle warns we might become if we take our networked lives too seriously, one who rages against real people in their lives and communities because a brand changed its website.

@dril, like Baudelaire, offers a social commentary rooted in the new material circumstances of our day-to-day lives. A profile of the account in The New Yorker encapsulates this view saying, “No longer just an icon of “Weird Twitter,” Dril has become one of America’s most incisive ongoing works of social criticism” (Marshall). Similar comments around the deeply-online quality of Weird Twitter can be seen in statements from accounts associated with the movement, such as the following from Buzzfeed New’s oral history article:

If I was a TED talk guy I would say that they're "hacking" Twitter. Or like "socially hacking" it or something. Is there a word for that? Like they've figured out how it works so perfectly that they can push it to its absolute limit. (@max_read, Herrman & Notopoulos)

This is how Weird Twitter resists the inauthenticity of networked life, it makes us laugh at an image of online existence pushed to its absolute limit, and in recognizing and identifying its contexts we become aware of our own relationship to that same sphere. At its most poignant and cathartic Weird Twitter presents us with micropoetries that meaningfully subvert or criticize how we are supposed to behave online. In engaging with them, identifying their absurdity, and finding them funny, we, consciously or unconsciously, define our own relationship to the online world. Laughing at @dril’s depiction of being a true brand “follower” affirms the idea that it would be unthinkable for us to hurt an animal because of something that happened online. @dril reveals online life to be absurd, and by extension reinforces the need to locate meaning in our actual lives.

The second way in which Weird Twitter subverts the hegemonic direction of online life is the deeply political undertone to much of the absurdist humor that it produces. Corporate and mainstream users who attempt to seriously cultivate a “brand image” for themselves are frequently mocked or parodied in Weird Twitter posts. The creator of the @dril account specifically locates the start of Weird Twitter in mocking corporate brand accounts:

“As for this "Weird Twitter" phenomenon, I believe it's simply a label that many people in social media loosely attach to a movement of ironic, satirical posts pioneered by the account "@kfc_colonel". Nobody knows who operates this account, but for years he has been impersonating a dead fast food mogul and asking his followers bizarre personal questions, usually regarding their consumption of KFC products. His influence inspired comedians to further the movement by creating accounts of a similar vein, such as "@Pepsi", "@Pizzahut", and "@mtn_dew", to name a few. I would suggest checking these guys out if you're into some real subversive social commentary.” (@dril, Herrman & Notopoulos)

This irreverence towards corporate online presence in the early days of Weird Twitter informs a broader progressive undertone to much of its content. Brand accounts, advertisers, influencers, billionaires, tech and media proponents, neoliberal and conservative politicians, and alt-right or similarly toxic online communities are all frequently the target of Weird Twitter humor. This often takes the form of “trolling”, in which a post disingenuously presents itself as in favor of these targets while incorporating childish crudity or surreal internet-addled abstractions to undermine its points. By leveraging the profoundly damaging inauthenticity of our networked lives as a source of humor, Weird Twitter accounts are necessarily also aware of the market forces that seek to maintain or manipulate that engagement with networked life.

Put it this way — I don't know anyone who's genuinely funny who doesn't also care about stuff. Some people just aren't interested in discussing politics explicitly. I think trolling is always political, but not in terms of Democrats vs Republicans or whatever. Trolling is one of those acts that is a statement in itself. It's a statement about people's attitudes and how they interact with the internet. (@methadonna, Herrman & Notopoulos)

An excellent example of this sort of earnest socio-political commentary by way of parody is @dasharez0ne’s. By juxtaposing an exaggerated parody of hyper-masculine meme formats with statements of personal sincerity and sensitivity, or hard-left political slogans, @dasharez0ne offers a compelling deconstruction of toxic masculinity. The absurd joke that lies at the centre of the account is the impossibility of someone expressing themselves in a hyper-masculine or toxic way while still being an empathetic and caring person, something that @dasharez0ne’s tweets push us to recognize as we laugh at them.

In recognizing and critiquing the politicized nature of online spaces Weird Twitter is able to name one of the reasons we have found networked life so alluring: the vested interest of a massive conglomerate of monetized capital interests which, more and more, require us to shop, work, pay our bills, and communicate online. Not only to sell us products, but to extract data on our experiences to then be computed and packaged as further prediction products (I suggest reading Shoshana Zuboff’s work on Surveillance Capitalism for further details).

This is a key element of why we struggle to regulate our relationship to networked life, and one which Turkle neglects to touch upon. In her conclusion she asks “What are we missing in our lives together that leads us to prefer lives alone together?” (285). Yet this question, of our willingness to ascribe technology a meaning it does not have, is only part of the problem confronting the networked individual and is answered in part by Turkle’s aforementioned suggestion that online life gives us a sense of control over the threat of disappointment in genuine relationships. To this problem Turkle’s solution of looking inward and cultivating an ability to value solitude, deliberateness, and “being present” are precisely correct.

However, when one wishes to regulate their relationship to the internet one does so as a single individual against a massive conglomerate of capital interests. It is not only that we are missing things from our unnetworked lives, but those omissions are being deliberately exploited by the forces of capital. To pull ourselves away from the screen requires us not only to find something outside of it, but to adjust to life without the drip-fed dopamine hits of being told we have a new message through a user interface designed by a dozen top engineers, visual designers, and psychologists to entice us into addictive feedback loops. Weird Twitter users recognize this imbalance, and comment upon it in their mockery of these institutions. Some have even, at times, publicly aligned themselves for socialist and progressive causes, such as @dasharez0ne’s endorsement of Bernie Sanders. In her survey of micropoetries Maria Denton suggests that this type of context-heavy para-literary work tends to arise out of communities on the margins of power and visibility, which is precisely how Weird Twitter is positioned against the market forces it critiques (3). That these accounts operate within the context of corporate-owned digital platforms is a core part of what makes their work meaningfully subversive, both for the way in which they undermine the influence of capital interests in these online spaces, as well their ability to connect with individual users through a shared understanding of our regular digital haunts.

This irreverence and defiance towards the technology capitalism is clearly resonant for their audiences, as accounts associated with the Weird Twitter movement have had an outsized influence on Twitter’s culture. At the time of writing @dasharez0ne has 148,000 followers, while @dril has 1.7 million. The progressive, “punching upward” political dimension of the humor contained on these accounts is a core aspect of their appeal, and helps us as internet-users to engage with the online environment in a self-aware and thoughtful way. If Weird Twitter highlights the ways in which neoliberal capitalist market forces are shaping and encroaching upon our experience of the web, it also provides us with a model of resistance to this force: laughter and derision.

Weird Twitter therefore constitutes a comedic genre and artistic movement of micropoetries that finds humor in an incisive understanding of networked life. Through parody and absurdity, Weird Twitter accounts highlight the way in which our experiences online are both inauthentic and compromised by the forces of capital. They offer an avenue of resistance to the negative impact of our networked lives that is distinct from, and I believe complimentary to, the model of personal mindfulness that Turkle proposes in Alone Together. Our anger, humor, playfulness and derision are just as important in placing boundaries on our networked lives as our thoughtfulness.

In order to redefine our relationship to 21st century technology we must find meaning outside of our screens as well as recognize the way in which we are being manipulated through them by capital interests. As we confront the challenge of building meaningfully close relationships with the people around us, we can at least find some catharsis in laughing at someone posting:

i’m going to beat the shit out of asimo.im gping to knock it on its ass while its trying to use a staircase at a trade show. dreadful beast (Dril, 333)

References:

Damon, Maria. “Micropoetries.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, 24 May 2017, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.63.

Dril. Dril Official Mr. Ten Years Anniversary Collection. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018.

Eiland, H., and M.W Jennings, editors. “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire.” Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings: Volume 4: 1938-1940, by W. Benjamin, Harvard University Press, 2003, pp. 3–93.

Freeman, Hadley. “Patricia Lockwood: 'That's What's so Attractive about the Internet: You Can Exist There as a Spirit in the Void'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 30 Jan. 2021, www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jan/30/patricia-lockwood-thats-whats-so-attractive-about-the-internet-you-can-exist-there-as-a-spirit-in-the-void.

Gallagher, Brenden. “A Survey of the Best and Weirdest of Weird Twitter.” Complex, Complex, 17 Apr. 2020, www.complex.com/pop-culture/2014/07/a-survey-of-the-best-and-weirdest-of-weird-twitter/kibblesmith.

Hathaway, Jay. “The Staggering Genius of Da Share Z0ne, 2016's Best Twitter Account.” The Daily Dot, 5 July 2016, www.dailydot.com/unclick/in-praise-of-da-share-z0ne/.

Herrman, John, and Katie Notopoulos. “Weird Twitter: The Oral History.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 5 Apr. 2013, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/jwherrman/weird-twitter-the-oral-history.

Laidler, John. “Harvard Professor Says Surveillance Capitalism Is Undermining Democracy.” Harvard Gazette, Harvard Gazette, 4 Mar. 2019, news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/03/harvard-professor-says-surveillance-capitalism-is-undermining-democracy/.

Love, Dylan. “Inside the Odd and Hilarious Subculture of 'Weird Twitter'.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 15 Dec. 2012, www.businessinsider.com/weird-twitter-2012-12.

Marshall, Colin. “The Cracked Wisdom of Dril.” The New Yorker, 17 June 2022, www.newyorker.com/culture/rabbit-holes/the-cracked-wisdom-of-dril.

Purdom, Clayton. “Following Dril, the Twitter Account at the End of the World.” The A.V. Club, 19 Oct. 2017, www.avclub.com/following-dril-the-twitter-account-at-the-end-of-the-w-1819327846.

Rosenberg, Sam. “The Wonderfully Weird World of ʻWeird Twitter'.” The Michigan Daily, 18 Jan. 2017, www.michigandaily.com/arts/wonderfully-weird-world-weird-twitter/.

Seigel, Jerrold E. Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830-1930. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Stephen, Bijan. “@Dril Is the Best Chronicler of the Internet's Last Decade.” The Verge, The Verge, 27 Sept. 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/9/27/17907568/dril-book-official-mr-ten-years-anniversary-collection-review-tweets-twitter.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, 2017.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Profile Books, 2019.